By John Walubengo

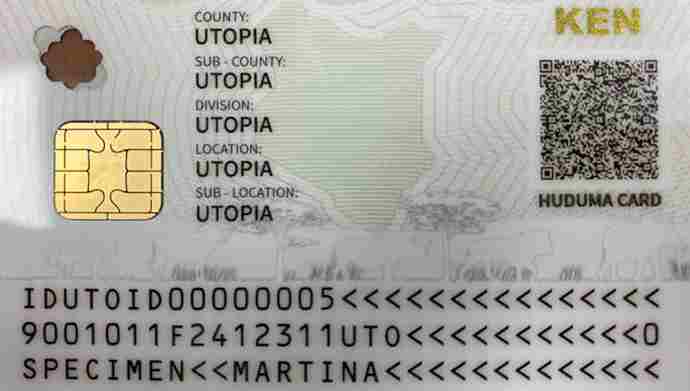

The 2019 KE Blockchain and AI report had digital ID as one of its key recommendations. Having a unique digital ID per citizen or resident is an important clog in the digital economy ecosystem.

It increases trust online and improves service delivery, convenience and efficiency since manual processes can be safely executed online. This is particularly true for government services that tend to have legal backing based on the identity of the people executing the transactions.

These issues have been covered severally on this platform and several policy papers written around them.

But for some reason, and despite the pros of having a digital ID, several years later and several attempts later, the Digital ID project still seems to get challenged in court again and again.

Whereas I am not privy to the details of the court petition, a panel sitting in the recent launch of another policy paper on digital IDs, seemed to suggest that the same issues facing the new Maisha Namba in court today were the very same ones that faced the aborted Huduma Namba project.

Unable to learn from the past?

Is it that we are unable to learn from our previous challenges, court rulings, and other past experiences? Some basic expectations, like the need to conduct and have a Data Protection Impact Assessment, had not been met by the time the government went on to pilot the project.

Contrary to popular opinion, it is possible to deploy a digital ID system that takes care of both the privacy issues of individuals as well as the national interests that the government is pursuing.

Issues of privacy are quite basic and well covered under the Data Protection Act, let us just comply, if we don’t, then human rights activists have a reason to wonder about the more complicated issues around potential discrimination, exclusion, and lack of accountability, amongst others.

All digital platforms are inherently discriminatory and exclusive by design; this is not something unique to government systems. Indeed, even the current and highly successful eCitizen platform can be argued to be discriminatory to the minority blind, even as it provides useful services to the majority of Kenyans.

It is therefore not surprising that minority groups like the Nubian communities and others that have been discriminated against for so long in the ‘offline world’ are apprehensive about the safeguards—if any—that exist to ensure that this offline discrimination does not get baked into the new digital ID system.

More concerns

Additionally, there are concerns around the ‘meta-data’, that is the data about the main data that gets generated each time transactions are performed using the digital ID.

When you log into any digital platform, your digital footprint describing when, how, and why you logged in gets automatically generated and provides fertile ground for data mining activities.

There is nothing wrong with data mining – as long as it is transparently clear who is doing the data mining and for what purpose. Additionally, there should be third-party oversight mechanisms, perhaps the Data Commissioner, to regularly audit and provide assurance that the original purpose is not being changed or extended illegally.

In conclusion, national digital IDs offer potential benefits; however, careful consideration of these key concerns is vital to ensuring that they are implemented ethically, securely, and inclusively. Open public dialogue, robust safeguards, and independent oversight are crucial to building trust and ensuring the responsible use of these powerful systems.

John Walubengo is an ICT Lecturer and Consultant. @jwalu.

![]()

The training is very good nd fantastic

the training has changed me positively by

1.adding more digital knowledge

2 creating employment I can now get extra coin in the pocket

3.the community has been empowered digitally

4.have been branded digital teacher in the community

5.digital knowledge has saved time, money, accidents because there is no congestion in cyber nowda people are operating at home

6.digital knowledge has reduced incidents of people being conned because of cyber crime knowledge they have gotten to ensure they have strong password,and don’t share important information anyhow

7.digital knowledge has reduced crime rate because youths are nowadays busy with data collection and empowering community

8.digital training has given me more data collection knowledge